Between skyrocketing costs, sport specialization and coaches needing training, youth sports is in the midst of a crisis, according to new data published Wednesday by the Sports & Fitness Industry Association and the Aspen Institute.

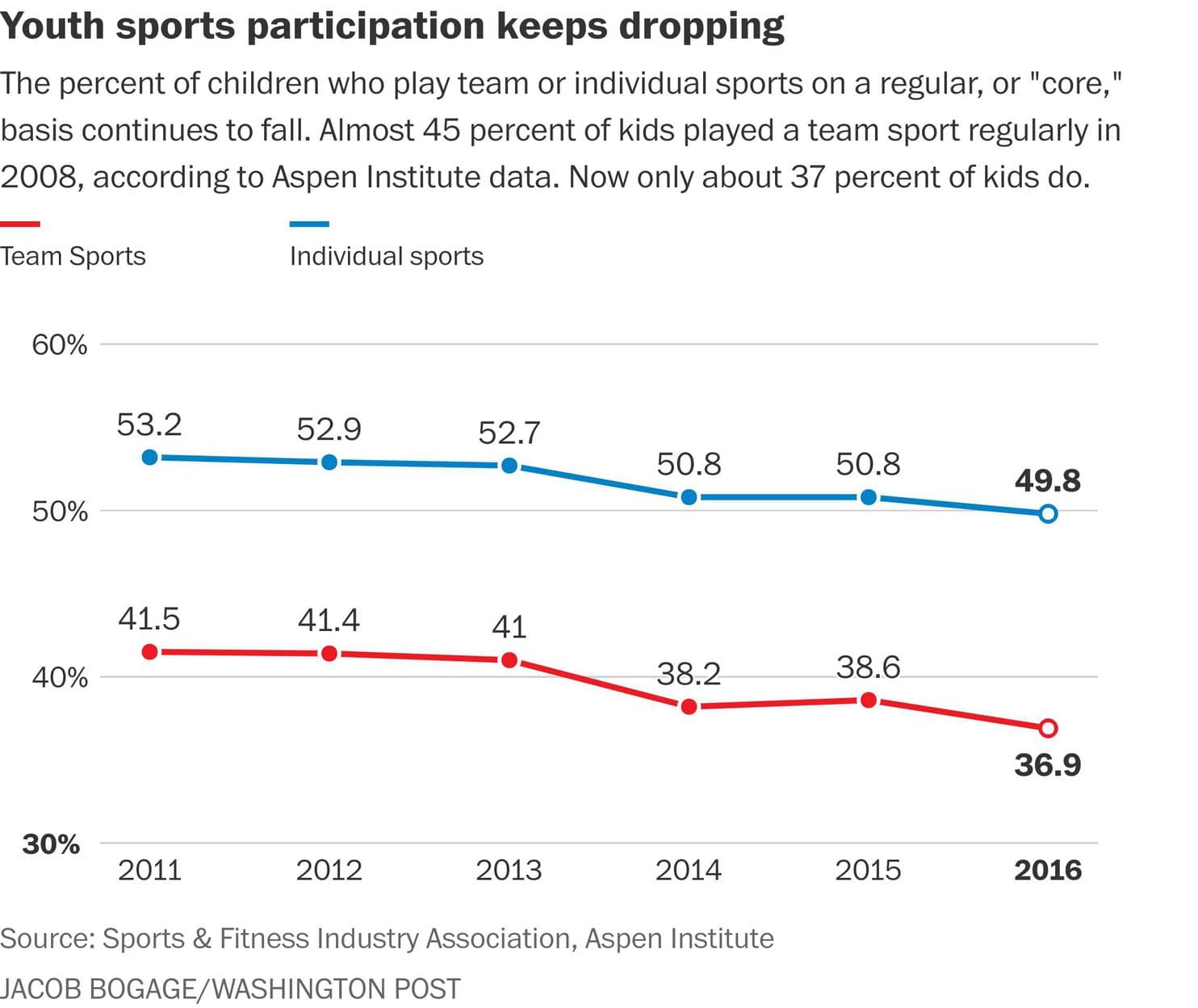

Athletic participation for kids ages 6 through 12 is down almost 8 percent over the last decade, according to SFIA and Aspen data, and children from low-income households are half as likely to play one day’s worth of team sports than children from households earning at least $100,000.

“Sports in America have separated into sport-haves and have-nots,” said Tom Farrey, executive director of Aspen’s Sports & Society program. The group released its research at its annual Project Play Summit on Wednesday in Washington. “All that matters is if kids come from a family that has resources. If you don’t have money, it’s hard to play.”

[In Neiko Primus, the world sees a basketball phenom. His mom sees a kid with only one childhood.]

Almost 45 percent of children ages 6 to 12 played a team sport regularly in 2008, according to Aspen data. Now only about 37 percent of children do.

Experts blame that trend on what they call an “up or out” mentality in youth sports. Travel leagues, ones that can sometimes cost thousands of dollars to join, have crept into increasingly younger age groups, and they take the most talented young athletes for their teams.

The children left behind either grow unsatisfied on regular recreational teams or get the message that the sport isn’t for them, Farrey said.

One of the summit’s main goals is to enable informal play and encourage kids to play more than one sport. Aspen, a nonprofit think tank, introduced a partnership with Major League Baseball, the NBA, Nike and a dozen other industry groups to pursue those strategies.

MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred, the keynote speaker, said he had spoken with the NBA, NFL and NHL commissioners and they agreed, “the best athlete is a kid who played multiple sports.”

But pursuit of a college athletic scholarship has “reshaped” the youth sports landscape, Farrey said, and placed an earlier emphasis on winning and elite skill development that often forces children to select one sport at an early age.

That has pushed hypercompetitive selection processes into younger age groups – some basketball analysts rank the nation’s best kindergartners – and ravaged traditional recreational leagues whose purpose is to get kids playing rather than winning games.

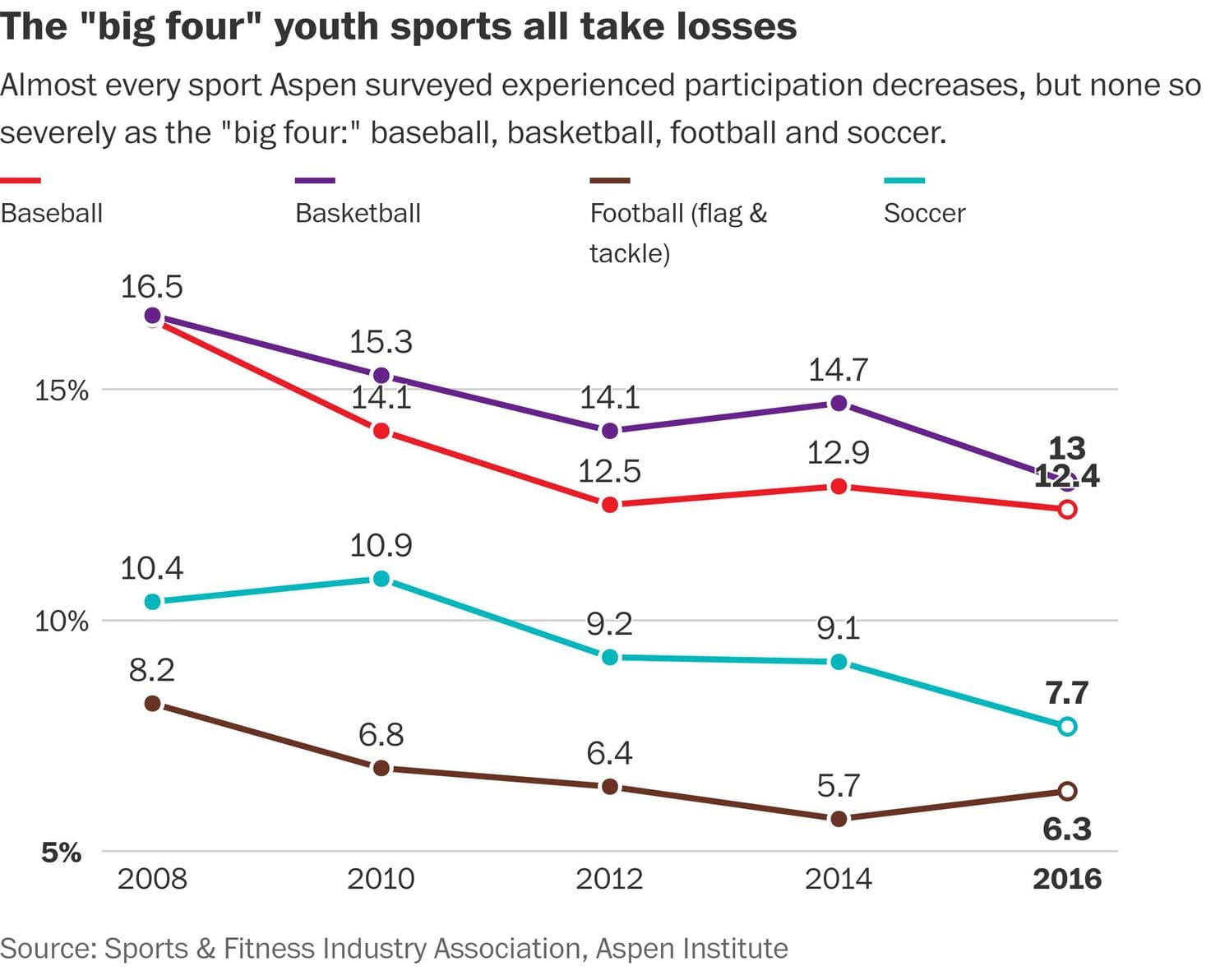

That has caused major losses for the “big four” American youth sports: baseball, basketball, soccer and football (both tackle and flag). Those four sports have suffered the most severe losses of any of the 15 team sports SFIA and Aspen surveyed.

The only sports that saw growth over the past eight years were golf, gymnastics, ice hockey and track and field.

Those declines have sent leagues and the nonprofits that support them scrambling to attract kids’ attention — often away from video games — and sweeten the deal for parents who sign their kids up for sports.

“We go out and we have to sell our program whether we charge or not,” said Lawrence Cann, founder of Street Soccer USA, a nonprofit that develops local soccer clubs.

“You can’t stick a kid in right field and he touches the ball once or twice a game,” Farrey said. “That’s not the same level of excitement as you can get on a video game.”

But money, measured in average household income, is the largest indicator of whether a child is going to be physically active or play sports, the data shows.

And whether children are physically active, Farrey said, is another of the largest indicators as to what kind of adult that child will become.

“There’s reams and reams of research on this,” he said. “Kids who are physically active are less likely to be obese. They’re better in the classroom. They go to college. They’re more likely to be active parents. And because of that, their kids are more active.”

Youth sports make up a $15 billion industry, according to a recent Time Magazine cover story, between costs for equipment, uniforms, travel, lodging, registration fees and so much more. And as elite travel teams reach into younger age groups, coaching often becomes privatized, too.

“There’s been this presumption that youth sports are exploding in this country and private clubs and trainers will pick up the slack,” Farrey said. “For kids with resources, they have. But families without resources are getting left behind.”

And those travel teams and private skills coaches can also drive up costs for traditional rec leagues, experts say.

Teams are in a constant fight for practice space, especially in urban areas, and affluent leagues often outbid rec leagues for use of the best fields in the most convenient locations, said former San Antonio mayor Ed Garza, now the president of the Urban Soccer Leadership Academy.

Another of the largest challenges facing youth sports: finding qualified coaches. According to SFIA and Aspen data, seven in 10 youth sports coaches are not trained in six core competencies required to be a qualified coach. Those competencies are general safety and injury prevention, effective motivational techniques, CPR and basic first aid, physical conditioning, concussion management, and sport-specific skills and tactics. At the summit, Aspen described the issue as a public health concern.

There is also barely any diversity in the youth coaching ranks. More than 70 percent of youth coaches for both boys’ and girls’ sports are male. Half of all coaches’ households make at least $100,000 per year.

Farrey said those kinds of trends make sports look like they are for some kids, those with enough money and superior skill, and not everyone. He hopes Aspen’s new coalition of sport organizations will help more kids gain access to fun athletic experiences.

“Success looks like every kid in this country having the opportunity to play sports,” he said, “and develop habits of physical activity for their lifetime.”

by Jacob Bogage

September 6, 2017