“Hey, data data — swing!”

COMPETITIVE YOUTH SPORTS may be as American as apple pie, but we know a lot less about youth sports than we do about apple pie.

The problem is that while the FDA takes responsibility for knowing everything about our food (as the EPA does with the environment and a group called ARDA does with religious life), no one agency or organization monitors youth sports either as a central part of American childhood or as an industry. (And it is an industry. The Columbus Dispatch reviewed tax returns in 2009 and found that nonprofit sports groups alone, from the AAU to the thousands of cash-strapped parent-run community leagues, have $5 billion a year pass through their coffers.) So we are left with a Wild West of local and regional organizations in dozens of sports and no better odds of getting pinpoint data than of counting all the tumbleweeds blowing across the land.

Yet research has been done; there are smart academics and organizations in search of answers. As part of ESPN’s summer 2013 Kids in Sports focus, we mined the often hidden-away data to paint as comprehensible a portrait of the nation’s competitive youth sports landscape as we could.

1. Youth sports is so big that no one knows quite how big it is.

How many American kids play competitively on teams or clubs? No one has ever conducted a census. Still, it’s worth looking at the various counts, even if they all are flawed.

For starters, the Sports and Fitness Industry Association (SFIA), which employs tens of thousands of online interviews, tallies how many kids between 6 and 17 are regular/frequent (or what it calls “core”) players of different sports. These “core” numbers make a decent stand-in for kids who play on organized teams, even though that’s not the question asked; what’s asked is whether a kid played that sport a minimum of 13 times a year in a sport like ice hockey or 26 times a year in a sport like soccer. SFIA gave ESPN The Mag custom data totaling up its 2011 participation.

That adds up to 21.47 million kids between 6 and 17, or more than the population of Texas in 2000. That’s big.

Competitive sports look bigger in a survey of students done by Don Sabo, a longtime youth-sports researcher and a professor at D’Youville College in Buffalo. He queried a research sample of 2,185 students in 2007 for the Women’s Sports Foundation and found that 75 percent of boys and 69 percent of girls from 8 to 17 took part in organized sports during the previous year — playing on at least one team or in one club. Do the math on the 39.82 million U.S. students ages 8 to 17 in 2011 and that would be 28.7 million of them playing organized sports, more than the population of Texas today plus most of Oklahoma. This chart shows the participation rate of Sabo’s sample.

Whichever estimate you have faith in, it’s far below the actual total, because it doesn’t count the millions of kids who start before age 6 or 8.

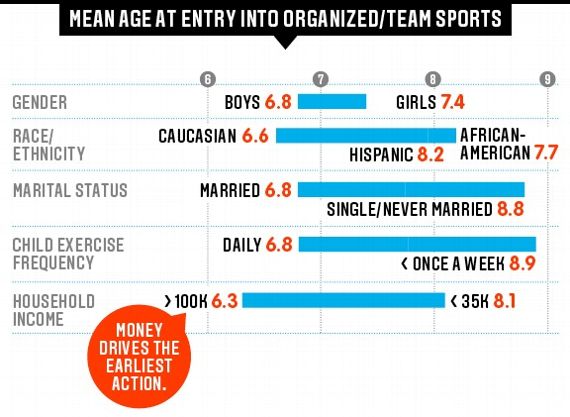

2. Kids start by kindergarten, unless …

No research tries to count the 2-year-olds everywhere being taught by their dads to shoot like Trick Shot Titus of Jimmy Kimmel fame or the 4-year-olds playing in Itty-Bitty and Munchkins leagues that let parents stand by their kids during the games. But Don Sabo’s research for the Women’s Sports Foundation does try to catch early starters, and it confirms what you already sense, either because you’re a parent or you drive by fields filled with them: Lots of kids start playing on teams before they start attending school.

But which kids? Sabo’s analysis distinguishing the early starters from the students who don’t begin until third or fourth grade speaks to several unsurprising truths about youth sports. Girls start an average of half a year later than boys, and kids who don’t exercise start later than those who do. But we also see starkly what drives the very earliest action: money. The biggest indicator of whether kids start young, Sabo found, is whether their parents have a household income of $100,000 or more.

And you know where most of those families live, right?

3. The suburban soccer mom (and dad) is based in fact.

Indeed, Sabo’s WSF data paints a distinct picture of suburbs where swaths of kids in elementary and middle school, especially boys, play on three, four or five teams, and the culture revolves around their practices, tourneys and getting to their games. In contrast, childhood in cities and rural areas isn’t as intensely sports-focused.

The suburbs clearly aren’t alone in their obsession: Kids all over America play sports, which means a large portion of families focus on youth sports. Ninety percent of parents with children on a team attend at least one of their kid’s games a week. And with youth players mostly at the age when they’ll still talk to parents, you can guess what the subject of conversation often is: 68 percent say they talk at least every other day about games and practices.

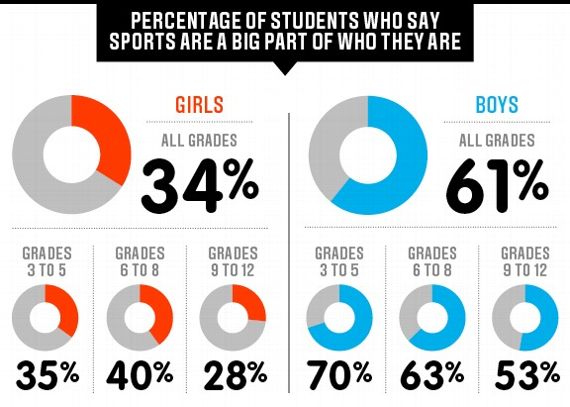

As involved as they are, though, parents aren’t necessarily driving the sports ship. Sabo asked kids whether sports are “a big part of who they are,” and the results reinforce just how deeply most American kids care about sports.

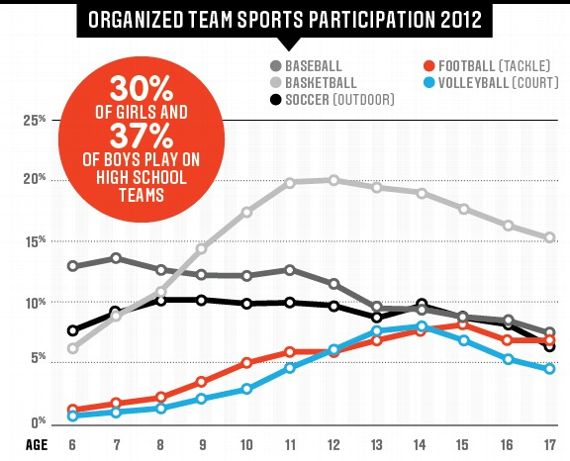

4. Hoops is the king because it’s for girls too.

Baseball and soccer start off fast, but by the time kids reach age 9, basketball becomes the most popular competitive sport, according to the SFIA’s regular/frequent count. Meanwhile, two sports played largely by one gender — football for boys and volleyball for girls — grow fast from ages 11 through 14 but never come close to catching up.

Even through age 17, basketball remains dominant because both genders continue to play organized ball. In a study done for the United States Tennis Association Don Sabo looked at data from 2006 to 2010 via an annual survey of about 50,000 students a year and found that 40 percent of adolescent boys and 25 percent of girls play competitive hoops. Soccer and track are the next most popular with both boys and girls, followed by swimming.

5. Dropping out is both the norm and often temporary.

Nervous types appalled by the incessant yelling by adults from the sidelines can be excused for believing that all the competition turns off as many kids as it turns on. Sabo found that 45 percent of the students in his survey who started a sport had quit it. Yet as you can see, the reasons for quitting aren’t that youth sports are necessarily bad.

Indeed, most of their reasons relate more to temporary concerns: The kids weren’t having fun playing, were hurt, didn’t get along with the team or wanted to focus on their studies. That sheds light on the report’s next finding: 33 percent of kids had restarted a sport they’d quit. Kids remain drawn to sports.

It helps that the trend has been toward offering more sports; using 2005-06 data, the WSF found that high schools had more teams for both girls and boys than they did in 2000. To wit, Sabo and his colleague Philip Veliz counted 2.3 million girls and 2.9 million boys playing on high school teams (public and private) in 2011-12 — 30 percent of high school girls and 37 percent of high school boys.

But there’s another trend as well: Millions of high school kids phase out organized sports, with the biggest drop-off coming early — during and after freshman year. High school sports can be competitive and involve roster cuts and commitments some teenagers can’t make. Kids quit for all the reasons above. Whatever the explanation, the numbers are sizable: SFIA reports that between ages 14 and 15 there’s a 26 percent drop in the number of kids who play at least one sport even casually.

6. In fact, the closer you look, the more you see the kids left behind.

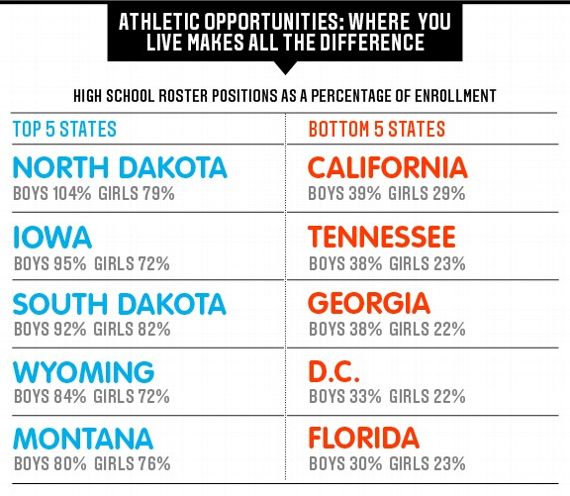

Girls continue to simply have less access. Whereas high schools in 31 states had enough roster slots for at least 50 percent of the boys enrolled, high schools in only 18 states had that many roster slots for girls.

And then there are the kids who live in the wrong places. In New York, a state with well-funded schools, high school teams could accommodate 75 percent of boys and 62 percent of girls. But high schools in budget-deprived California and Florida, two other major states, had spots on teams for only 29 percent and 23 percent of girls, and 39 percent and 30 percent of boys, respectively.

Meanwhile, opportunities for city kids are far fewer. In Washington D.C., the WSF found, high schools had positions on teams for only 22 percent of girls and 33 percent of boys. That’s about one-third the opportunity of girls in New York state and boys in North Dakota.

Living in poor corners of cities culls even more kids from sports. Nationwide, according to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, only a quarter of eighth- to 12th-graders enrolled in the poorest schools played school sports. (Those are schools with the highest rate of free-lunch eligibility, which are also among the schools with the highest dropout rates, meaning that even lower percentages of the kids in those communities are playing.) This situation won’t be helped as schools continue to cut back funds for teams. The percentage of high schools with no sports has already jumped from 8.2 percent during the 1999-2000 school year to 15.1 percent in 2009-10.

7. Finally, about our kids’ health …

The No. 1 fear of sports parents is seeing their child injured on the field. And due to the United States’ growing population and sports participation, that’s now more common. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, roughly 2.7 million kids under 20 were treated for “sports and recreation” injuries from 2001 to 2009.

Reports of head injuries are especially on the rise. From 2001 to 2009, emergency room visits for traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) among children under 19 rose 62 percent. And football concussions reported among 10- to 14-year-olds more than doubled from 4,138 in 2000 to 10,759 in 2010, according to the CDC.

Yet looking closely at the CDC’s traumatic brain injury data, which includes concussions, puts football in context. More kids go to emergency rooms with TBIs from biking accidents than from football hits, and the percentage of ER visits for TBIs in football (7.2 percent) was lower than in a bunch of sports, including soccer, baseball, hockey of all types, ice skating, ATV and dirt-bike riding and, most dangerous, horseback riding, where an ER visit is twice as likely to involve a brain injury than in football.

Long-term, the nation’s biggest health concern remains obesity. And despite all the youth leagues, the waistlines of America’s children are growing. According to the latest CDC numbers, 16.9 percent of kids were obese in 2009-10, almost triple the rate of 1980. According to the CDC, overweight children have a 70 percent chance of becoming overweight adults. By 2030, the CDC predicts that 42 percent of all American adults will be obese.

Clearly, all the time that kids spend competing — and that their parents spend urging them on — hasn’t forestalled the epidemic. It can’t help that for every extra hour kids who love to compete spend in uniform, they spend many more hours staring at a screen. In 2009, children spent more than 7 1/2 hours in front of some sort of media, from handheld devices to iPods to computers or TVs, according to the Kaiser Foundation.

For that and many other reasons, the transition from adolescence to early adulthood — from the time when the bulk of kids compete in sports to the time when most don’t — takes a measurable toll. Every year closer to age 18 our kids get, fewer of them are as physically active as they should be.

The ubiquity of competitive sports is clearly not a panacea, nor does it last. By 18, the youth-sports pipeline has reached a destination or sorts — by then Serena Williams had won her first major, Bryce Harper and Kobe Bryant had been drafted and Tiger Woods had teed it up for his first PGA tourney. The players largely have been sorted into their categories: future pros; college athletes; club and rec competitors; and those who give up.

Yet after all is said and done, one fact sticks out: Of all the kids in America, very few have not played sports. In the survey done by Sabo for the WSF, only 13 percent of boys and 18 percent of girls between 8 and 17 had never joined a team or club, had never shared the experience of getting a uniform, practicing with teammates and running onto the field or court to compete.

That’s American childhood for you.

by Bruce Kelley and Carl Carchia

July 11, 2013